Fundamental group

In mathematics, more specifically algebraic topology, the fundamental group or Poincaré group[1] (named after Henri Poincaré who gave the definition in his article Analysis Situs, published in 1895) is a group associated to any given pointed topological space that provides a way of determining when two paths, starting and ending at a fixed base point, can be continuously deformed into each other. Intuitively, it records information about the basic shape, or holes, of the topological space. The fundamental group is the first and simplest of the homotopy groups.

Fundamental groups can be studied using the theory of covering spaces, since a fundamental group coincides with the group of deck transformations of the associated universal covering space. Its abelianisation can be identified with the first homology group of the space. When the topological space is homeomorphic to a simplicial complex, its fundamental group can be described explicitly in terms of generators and relations.

Historically, the concept of fundamental group first emerged in the theory of Riemann surfaces, in the work of Bernhard Riemann, Henri Poincaré and Felix Klein, where it describes the monodromy properties of complex functions, as well as providing a complete topological classification of closed surfaces.

Contents |

Intuition

Start with a space (e.g. a surface), and some point in it, and all the loops both starting and ending at this point — paths that start at this point, wander around and eventually return to the starting point. Two loops can be combined together in an obvious way: travel along the first loop, then along the second. Two loops are considered equivalent if one can be deformed into the other without breaking. The set of all such loops with this method of combining and this equivalence between them is the fundamental group.

For the precise definition, let X be a topological space, and let x0 be a point of X. We are interested in the set of continuous functions f : [0,1] → X with the property that f(0) = x0 = f(1). These functions are called loops with base point x0. Any two such loops, say f and g, are considered equivalent if there is a continuous function h : [0,1] × [0,1] → X with the property that, for all 0 ≤ t ≤ 1, h(t, 0) = f(t), h(t, 1) = g(t) and h(0, t) = x0 = h(1, t). Such an h is called a homotopy from f to g, and the corresponding equivalence classes are called homotopy classes.

The product f ∗ g of two loops f and g is defined by setting (f ∗ g)(t) := f(2t) if 0 ≤ t ≤ 1/2 and (f ∗ g)(t) := g(2t − 1) if 1/2 ≤ t ≤ 1. Thus the loop f ∗ g first follows the loop f with "twice the speed" and then follows g with twice the speed. The product of two homotopy classes of loops [f] and [g] is then defined as [f ∗ g], and it can be shown that this product does not depend on the choice of representatives.

With the above product, the set of all homotopy classes of loops with base point x0 forms the fundamental group of X at the point x0 and is denoted

or simply π(X, x0). The identity element is the constant map at the basepoint, and the inverse of a loop f is the loop g defined by g(t) = f(1 − t). That is, g follows f backwards.

Although the fundamental group in general depends on the choice of base point, it turns out that, up to isomorphism, this choice makes no difference so long as the space X is path-connected. For path-connected spaces, therefore, we can write π1(X) instead of π1(X, x0) without ambiguity whenever we care about the isomorphism class only.

Examples

Trivial fundamental group. In Euclidean space Rn, or any convex subset of Rn, there is only one homotopy class of loops, and the fundamental group is therefore the trivial group with one element. A path-connected space with a trivial fundamental group is said to be simply connected.

Infinite cyclic fundamental group. The circle. Each homotopy class consists of all loops which wind around the circle a given number of times (which can be positive or negative, depending on the direction of winding). The product of a loop which winds around m times and another that winds around n times is a loop which winds around m + n times. So the fundamental group of the circle is isomorphic to  , the additive group of integers. This fact can be used to give proofs of the Brouwer fixed point theorem and the Borsuk–Ulam theorem in dimension 2.

, the additive group of integers. This fact can be used to give proofs of the Brouwer fixed point theorem and the Borsuk–Ulam theorem in dimension 2.

Since the fundamental group is a homotopy invariant, the theory of the winding number for the complex plane minus one point is the same as for the circle.

Free groups of higher rank: Graphs. Unlike the homology groups and higher homotopy groups associated to a topological space, the fundamental group need not be abelian. For example, the fundamental group of the figure eight is the free group on two letters. More generally, the fundamental group of any graph G is a free group. Here the rank of the free group is equal to 1 − χ(G): one minus the Euler characteristic of G, when G is connected.

Knot theory. A somewhat more sophisticated example of a space with a non-abelian fundamental group is the complement of a trefoil knot in R3.

Functoriality

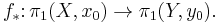

If f : X → Y is a continuous map, x0 ∈ X and y0 ∈ Y with f(x0) = y0, then every loop in X with base point x0 can be composed with f to yield a loop in Y with base point y0. This operation is compatible with the homotopy equivalence relation and with composition of loops. The resulting group homomorphism, called the induced homomorphism, is written as π(f) or, more commonly,

We thus obtain a functor from the category of topological spaces with base point to the category of groups.

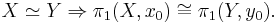

It turns out that this functor cannot distinguish maps which are homotopic relative to the base point: if f and g : X → Y are continuous maps with f(x0) = g(x0) = y0, and f and g are homotopic relative to {x0}, then f* = g*. As a consequence, two homotopy equivalent path-connected spaces have isomorphic fundamental groups:

As an important special case, if X is path-connected then any two basepoints give isomorphic fundamental groups, with isomorphism given by a choice of path between the given basepoints.

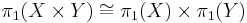

The fundamental group functor takes products to products and coproducts to coproducts. That is, if X and Y are path connected, then

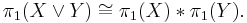

and

(In the latter formula,  denotes the wedge sum of topological spaces, and * the free product of groups.) Both formulas generalize to arbitrary products. Furthermore the latter formula is a special case of the Seifert–van Kampen theorem which states that the fundamental group functor takes pushouts along inclusions to pushouts.

denotes the wedge sum of topological spaces, and * the free product of groups.) Both formulas generalize to arbitrary products. Furthermore the latter formula is a special case of the Seifert–van Kampen theorem which states that the fundamental group functor takes pushouts along inclusions to pushouts.

Fibrations

A generalization of a product of spaces is given by a fibration,

Here the total space E is a sort of "twisted product" of the base space B and the fiber F. In general the fundamental groups of B, E and F are terms in a long exact sequence involving higher homotopy groups. When all the spaces are connected, this has the following consequences for the fundamental groups:

- π1(B) and π1(E) are isomorphic if F is simply connected

- πn+1(B) and πn(F) are isomorphic if E is contractible

The latter is often applied to the situation E = path space of B, F = loop space of B or B = classifying space BG of a topological group G, B = universal G-bundle EG.

Relationship to first homology group

The fundamental groups of a topological space X are related to its first singular homology group, because a loop is also a singular 1-cycle. Mapping the homotopy class of each loop at a base point x0 to the homology class of the loop gives a homomorphism from the fundamental group π1(X, x0) to the homology group H1(X). If X is path-connected, then this homomorphism is surjective and its kernel is the commutator subgroup of π1(X, x0), and H1(X) is therefore isomorphic to the abelianization of π1(X, x0). This is a special case of the Hurewicz theorem of algebraic topology.

Universal covering space

If X is a topological space that is path connected, locally path connected and locally simply connected, then it has a simply connected universal covering space on which the fundamental group π(X,x0) acts freely by deck transformations with quotient space X. This space can be constructed analogously to the fundamental group by taking pairs (x, γ), where x is a point in X and γ is a homotopy class of paths from x0 to x and the action of π(X, x0) is by concatenation of paths. It is uniquely determined as a covering space.

Examples

Let G be a connected, simply connected compact Lie group, for example the special unitary group SUn, and let Γ be a finite subgroup of G. Then the homogeneous space X = G/Γ has fundamental group Γ, which acts by right multiplication on the universal covering space G. Among the many variants of this construction, one of the most important is given by locally symmetric spaces X = Γ\G/K, where

- G is a non-compact simply connected, connected Lie group (often semisimple),

- K is a maximal compact subgroup of G

- Γ is a discrete countable torsion-free subgroup of G.

In this case the fundamental group is Γ and the universal covering space G/K is actually contractible (by the Cartan decomposition for Lie groups).

As an example take G = SL2(R), K = SO2 and Γ any torsion-free congruence subgroup of the modular group SL2(Z).

An even simpler example is given by G = R (so that K is trivial) and Γ = Z: in this case X=R/Z = S1.

From the explicit realization, it also follows that the universal covering space of a path connected topological group H is again a path connected topological group G. Moreover the covering map is a continuous open homomorphism of G onto H with kernel Γ, a closed discrete normal subgroup of G:

Since G is a connected group with a continuous action by conjugation on a discrete group Γ, it must act trivially, so that Γ has to be a subgroup of the center of G. In particular π1(H) = Γ is an Abelian group; this can also easily be seen directly without using covering spaces. The group G is called the universal covering group of H.

As the universal covering group suggests, there is an analogy between the fundamental group of a topological group and the center of a group; this is elaborated at Lattice of covering groups.

Edge-path group of a simplicial complex

If X is a connected simplicial complex, an edge-path in X is defined to be a chain of vertices connected by edges in X. Two edge-paths are said to be edge-equivalent if one can be obtained from the other by successively switching between an edge and the two opposite edges of a triangle in X. If v is a fixed vertex in X, an edge-loop at v is an edge-path starting and ending at v. The edge-path group E(X, v) is defined to be the set of edge-equivalence classes of edge-loops at v, with product and inverse defined by concatenation and reversal of edge-loops.

The edge-path group is naturally isomorphic to π1(|X|, v), the fundamental group of the geometric realisation |X| of X. Since it depends only on the 2-skeleton X2 of X (i.e. the vertices, edges and triangles of X), the groups π1(|X|,v) and π1(|X2|, v) are isomorphic.

The edge-path group can be described explicitly in terms of generators and relations. If T is a maximal spanning tree in the 1-skeleton of X, then E(X, v) is canonically isomorphic to the group with generators the oriented edges of X not occurring in T and relations the edge-equivalences corresponding to triangles in X containing one or more edge not in T. A similar result holds if T is replaced by any simply connected—in particular contractible—subcomplex of X. This often gives a practical way of computing fundamental groups and can be used to show that every finitely presented group arises as the fundamental group of a finite simplicial complex. It is also one of the classical methods used for topological surfaces, which are classified by their fundamental groups.

The universal covering space of a finite connected simplicial complex X can also be described directly as a simplicial complex using edge-paths. Its vertices are pairs (w,γ) where w is a vertex of X and γ is an edge-equivalence class of paths from v to w. The k-simplices containing (w,γ) correspond naturally to the k-simplices containing w. Each new vertex u of the k-simplex gives an edge wu and hence, by concatenation, a new path γu from v to u. The points (w,γ) and (u, γu) are the vertices of the "transported" simplex in the universal covering space. The edge-path group acts naturally by concatenation, preserving the simplicial structure, and the quotient space is just X.

It is well-known that this method can also be used to compute the fundamental group of an arbitrary topological space. This was doubtless known to Čech and Leray and explicitly appeared as a remark in a paper by Weil (1960); various other authors such as L. Calabi, W-T. Wu and N. Berikashvili have also published proofs. In the simplest case of a compact space X with a finite open covering in which all non-empty finite intersections of open sets in the covering are contractible, the fundamental group can be identified with the edge-path group of the simplicial complex corresponding to the nerve of the covering.

Realizability

- Every group can be realized as the fundamental group of a connected CW-complex of dimension 2 (or higher). As noted above, though, only free groups can occur as fundamental groups of 1-dimensional CW-complexes (that is, graphs).

- Every finitely presented group can be realized as the fundamental group of a compact, connected, smooth manifold of dimension 4 (or higher). But there are severe restrictions on which groups occur as fundamental groups of low-dimensional manifolds. For example, no free abelian group of rank 4 or higher can be realized as the fundamental group of a manifold of dimension 3 or less.

Related concepts

The fundamental group measures the 1-dimensional hole structure of a space. For studying "higher-dimensional holes", the homotopy groups are used. The elements of the n-th homotopy group of X are homotopy classes of (basepoint-preserving) maps from Sn to X.

The set of loops at a particular base point can be studied without regarding homotopic loops as equivalent. This larger object is the loop space.

For topological groups, a different group multiplication may be assigned to the set of loops in the space, with pointwise multiplication rather than concatenation. The resulting group is the loop group.

Fundamental groupoid

Rather than singling out one point and considering the loops based at that point up to homotopy, one can also consider all paths in the space up to homotopy (fixing the initial and final point). This yields not a group but a groupoid, the fundamental groupoid of the space.

See also

- Homotopy group, generalization of fundamental group

There are also similar notions of fundamental group for algebraic varieties (the étale fundamental group) and for orbifolds (the orbifold fundamental group).

References

- Joseph J. Rotman, An Introduction to Algebraic Topology, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-96678-1

- Isadore Singer and John A. Thorpe, Lecture Notes on Elementary Geometry and Topology, Springer-Verlag (1967) ISBN 0-387-90202-3

- Allen Hatcher, Algebraic Topology, Cambridge University Press (2002) ISBN 0-521-79540-0

- Peter Hilton and Shaun Wylie, Homology Theory, Cambridge University Press (1967) [warning: these authors use contrahomology for cohomology]

- Richard Maunder, Algebraic Topology, Dover (1996) ISBN 0486691314

- Deane Montgomery and Leo Zippin, Topological Transformation Groups, Interscience Publishers (1955)

- James Munkres, Topology, Prentice Hall (2000) ISBN 0131816292

- Herbert Seifert and William Threlfall, A Textbook of Topology (translated from German by Wofgang Heil), Academic Press (1980), ISBN 0126348502

- Edwin Spanier, Algebraic Topology, Springer-Verlag (1966) ISBN 0-387-94426-5

- André Weil, On discrete subgroups of Lie groups, Ann. of Math. 72 (1960), 369-384.

- Fundamental group on PlanetMath

- Fundamental groupoid on PlanetMath

Notes

- ↑ Glen E. Bredon, Topology and Geometry, p. 132

External links

- Dylan G.L. Allegretti, Simplicial Sets and van Kampen's Theorem (An elementary discussion of the fundamental groupoid of a topological space and the fundamental groupoid of a simplicial set).

- Animations to introduce to the fundamental group by Nicolas Delanoue